The Journey

Dara*, She/Her“The world is bigger than you can imagine and will open up to you in time. So don’t worry so much. Your choices don’t all need to be understood, even by those close to you.”

|| CW: Needles

I went to a place called Zhongdian in southwest China, Yunnan Province. Now it's called Shangri-La to attract tourists. Every year they have Saima Jie, a Tibetan horse-riding festival, and I wanted to go there.

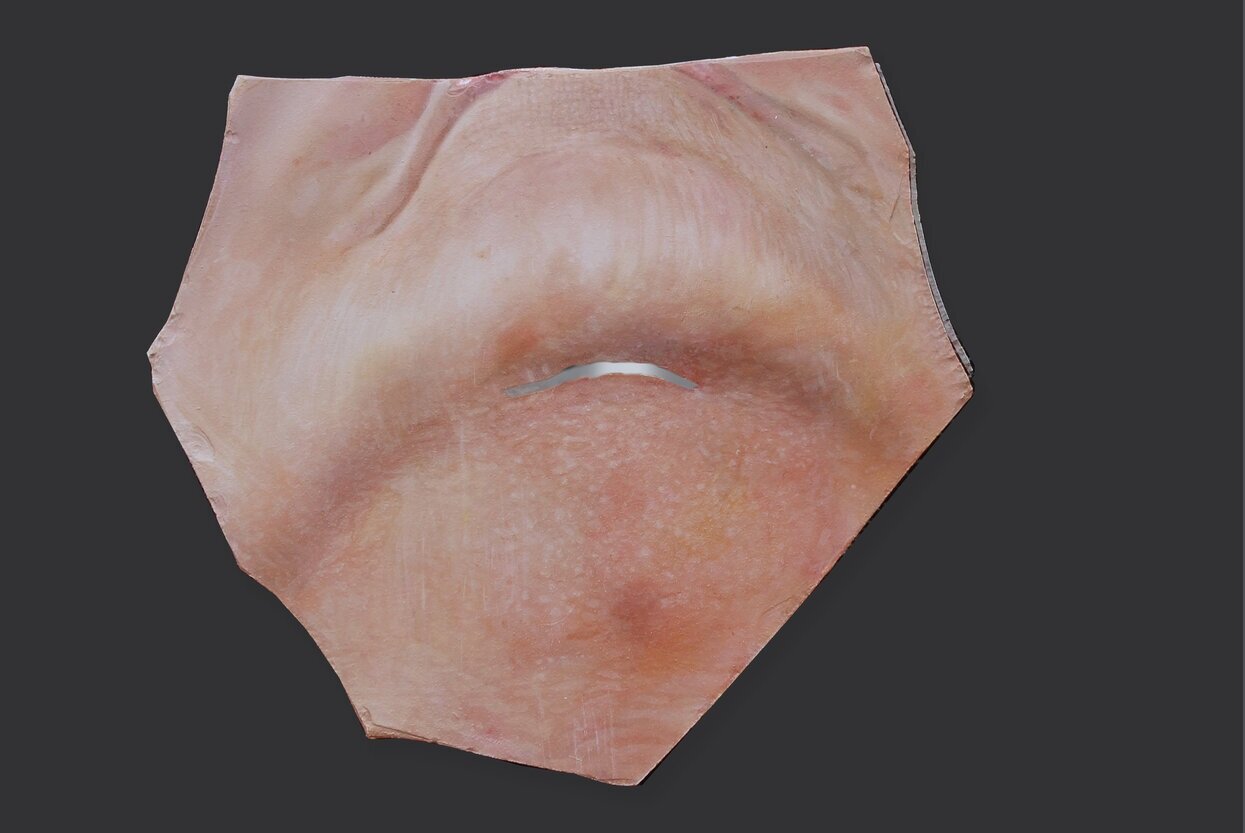

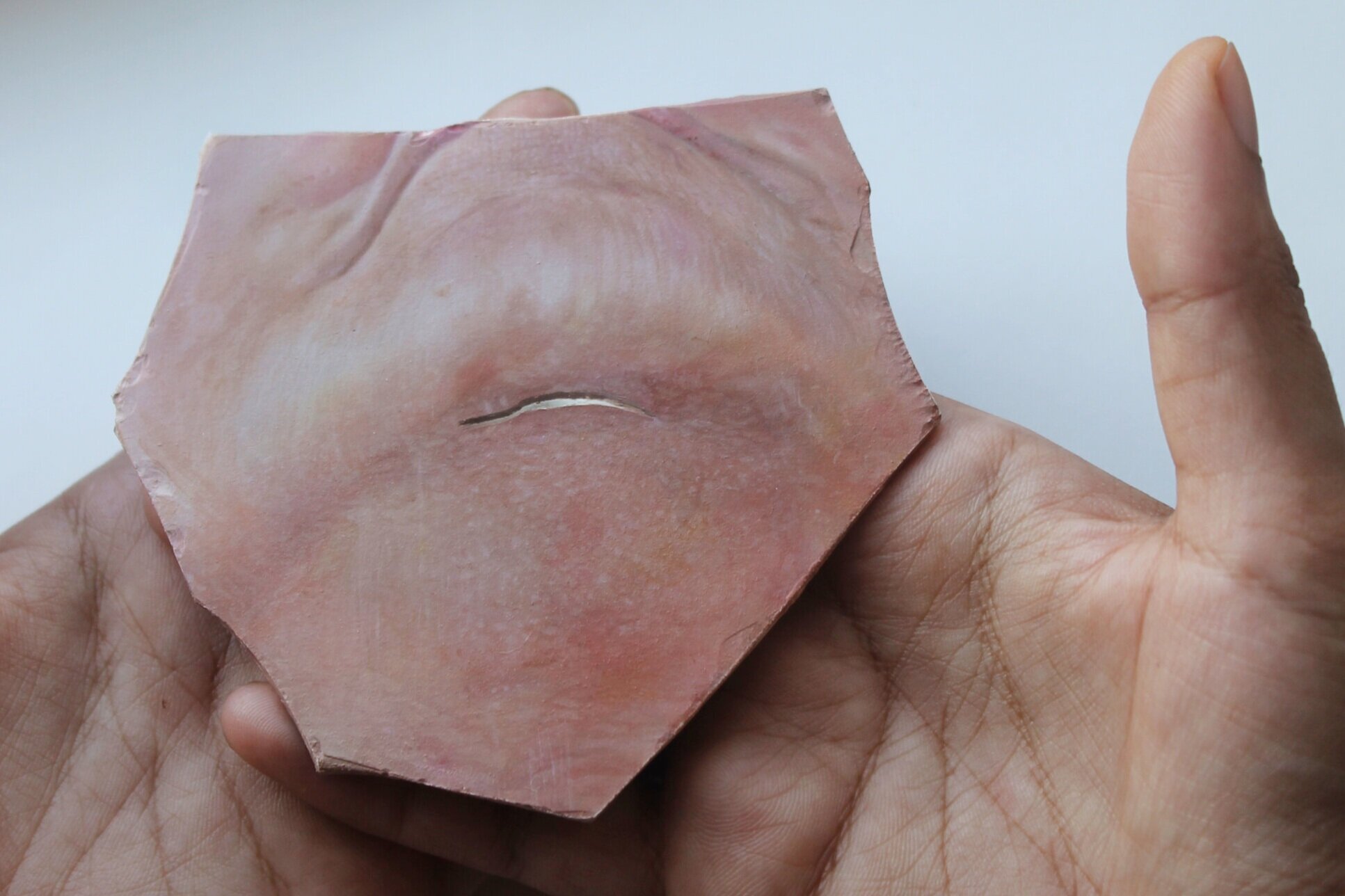

My friend and I wanted to go to the temple, and we rented a motorcycle taxi. I was in the sidecar. I don't know if this is true of all sidecars, but the glass windshield only went up to my nose. The roads were really rough. We hit a big rock, and the rock flew up and hit me right in the face, right here. We ended up having to go to the hospital because I was bleeding a lot.

I remember the hospital smelled like butter tea. The nurse started coming after me with a glass needle. One thing we were told before going to China at that time - because it's in the Southwest corner where there's a lot of heroin and opium trading - they said never use a glass needle because of AIDS. This nurse is coming at me with a glass needle towards my head, but I didn't know the word for sterilized in Chinese. My friend didn't know either.

The doctors said "If you come back within a certain number of hours, we can still stitch it. Otherwise, you're going to have a permanent scar." My friend's dad, as it turned out, was a surgeon and was visiting from New York City. So my friend said, "Well, my dad went hiking today, but maybe he'll do it. He'll stitch you up." We went back to the hostel, but [when we returned] they said he was still hiking up the mountain. Who knows when he would be back? I just waited and waited. Finally he returned and we got a regular taxi to the hospital. There was no electricity; it was getting dark. I had a headache. He sterilized a needle with alcohol and asked me to thread it because he couldn’t see so well. The sun was setting and he stitched it. They charged us about $3 (USD) for the materials. He did a great job but I did end up peeling the scab off so there’s still this scar.

At the time, I kind of saw it as a sign that I wasn't meant to go to that temple. I'm superstitious. Part of me thought they didn't want us to go to the temple. Maybe we were considered evil (laughs), bad auras or something. But looking back, it was not a big deal. You know, when you're injured and you're in a foreign place, you feel like it's horrible. But I did go back to a yellow hat temple three years ago, in another part of China, and it was fine.

I went initially to teach English. But then I found out my mom was from this tribal minority group called Yi. My third year in China, I wanted to go to her hometown. I heard they had a torch festival there. It's like their New Year's celebration that happens at the summer solstice. I got on a hard seat train where I had to stand the whole way- 10 plus hours- and went to the city but I couldn't find any trace of the festival. There were no posters, no proper preparations or anything. I found a travel agency and I told them I wanted to go to the torch festival. They were like, "Why? Who are you? What are you doing here?" All these questions because I was this young woman traveling alone. I was staying in a guesthouse, sharing a room with, I think, a prostitute. Then they said they called a relative and the relative came to that hotel, took me to their house. I don't know how they knew who my relative was, but I think they figured I was a descendent of one of the only families that immigrated to the US.

I was walking with this aunt to her apartment – I was really trusting back then – and there was a cop who came over. He said he had seen me earlier that day. And he said I looked strange, like I stuck out for some reason, but he didn't know why. And then he offered to take me to my mom's ancestral home up in the mountains. His last name was Najia and Najia is the word for Lung in Yi language, and my mom's name is Lung. So he was supposedly a really distant relative, but with the same last name. People in the clan intermarried, my grandparents were first cousins.

The trip took 10 days. We walked, rode tractors, buses, and a horse for the last haul. It's the only time in my life that I couldn't walk anymore. I was sitting down on a rock and I couldn't get up anymore. And he said, "If you can't get up, I'm going to carry you on my back." Because they do that there, don’t they? I got up, I told him, "You can carry my bag." He carried my bag, a good old Jansport backpack.

I took my mom there the following year. Government officials went with us and we took a jeep the whole way to the top of the mountain.

[The cop] said that there had always been a road, but he wanted me to experience the journey.

I was the first relative to come back. So they had a party. They sacrificed animals for you. So I remember I had several chickens, maybe a goat on the way there. And then the finale was a cow. They found an orange drink for me from a neighboring village, there were no stores nearby.

I slept in the house of my relatives. They have straw and mud homes with dirt floors with a big fire pit in the middle. Everything happens around that fire pit. And then a few straw beds on the side. I was sleeping on one of these straw beds and they woke me up around 3am and they said, "The Cow. They're gonna kill the cow. They brought the cow in from another village. You have to get up." And I had been eating meat, just meat, for 10 days. And I didn't go to the bathroom either for 10 days. Even with all that walking.

They made me watch the slaughter. Knife to the throat and then chopped it up. They fed me totoro, which is chunks of meat. Usually it's pork. There are two short stools placed, one for me and one for the old man of the village. Everyone else was squatting. Only all the men from the village were there and they kept giving me chunks of meat and I kept pretending to eat them. I said "kashasha," which means thank you in Yi, and then I threw them over my shoulder as everyone else did. Now there are all these bones accumulating on the ground. At the end of the night there were lots of bones then some random pieces in between full of meat still. It was so obvious that they were mine. If I was a painter, instead of a photographer, that image is forever planted in my head.

A young guy said that he planted a tree for my visit; I wonder if it’s still there.

|| CW: Eating Disorders

I was anorexic when I was 16 for a year and a half. I had a friend where for some reason we started going on a diet together. I wonder if since that's the years when you're still growing, if that affects your body when you're an adult.

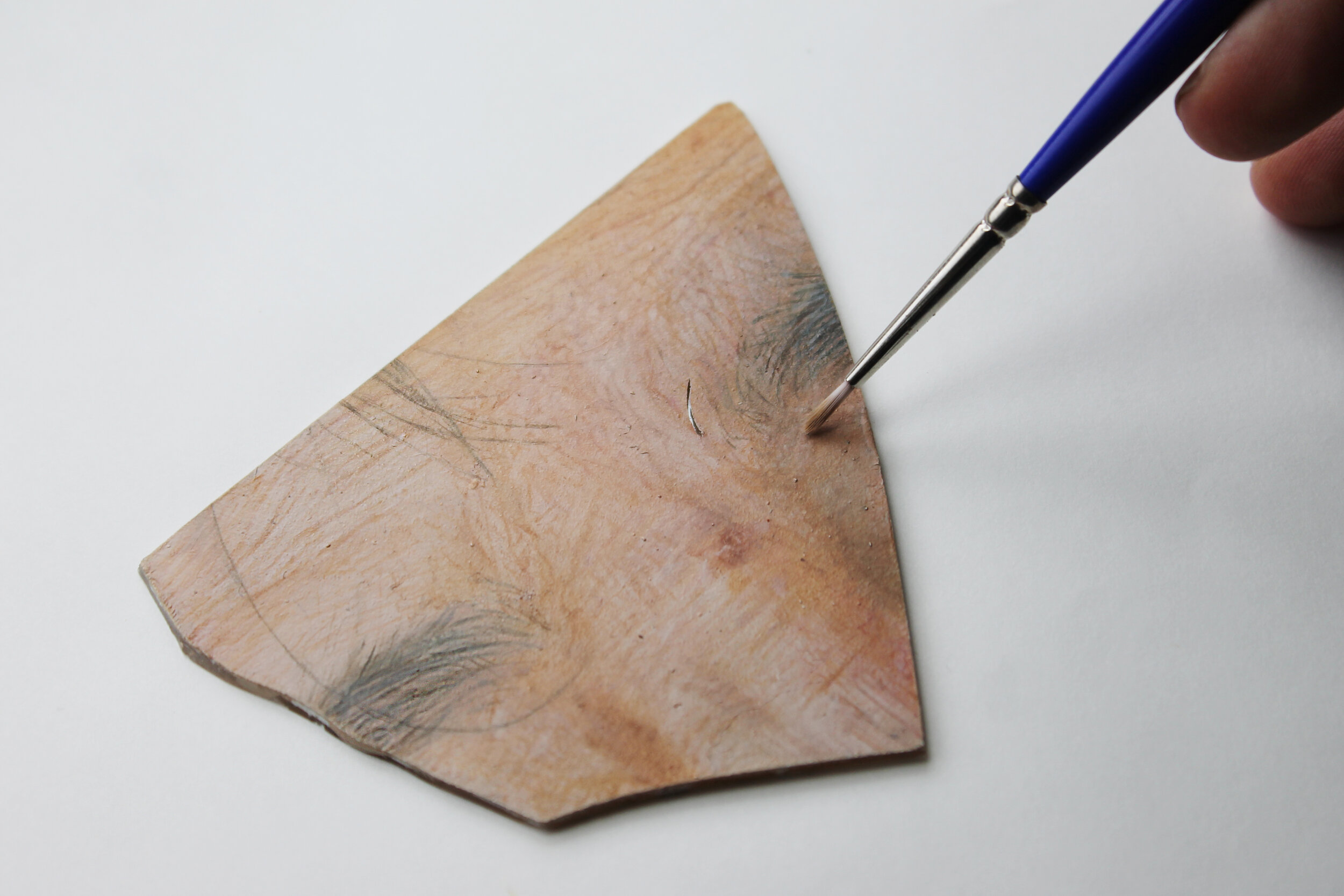

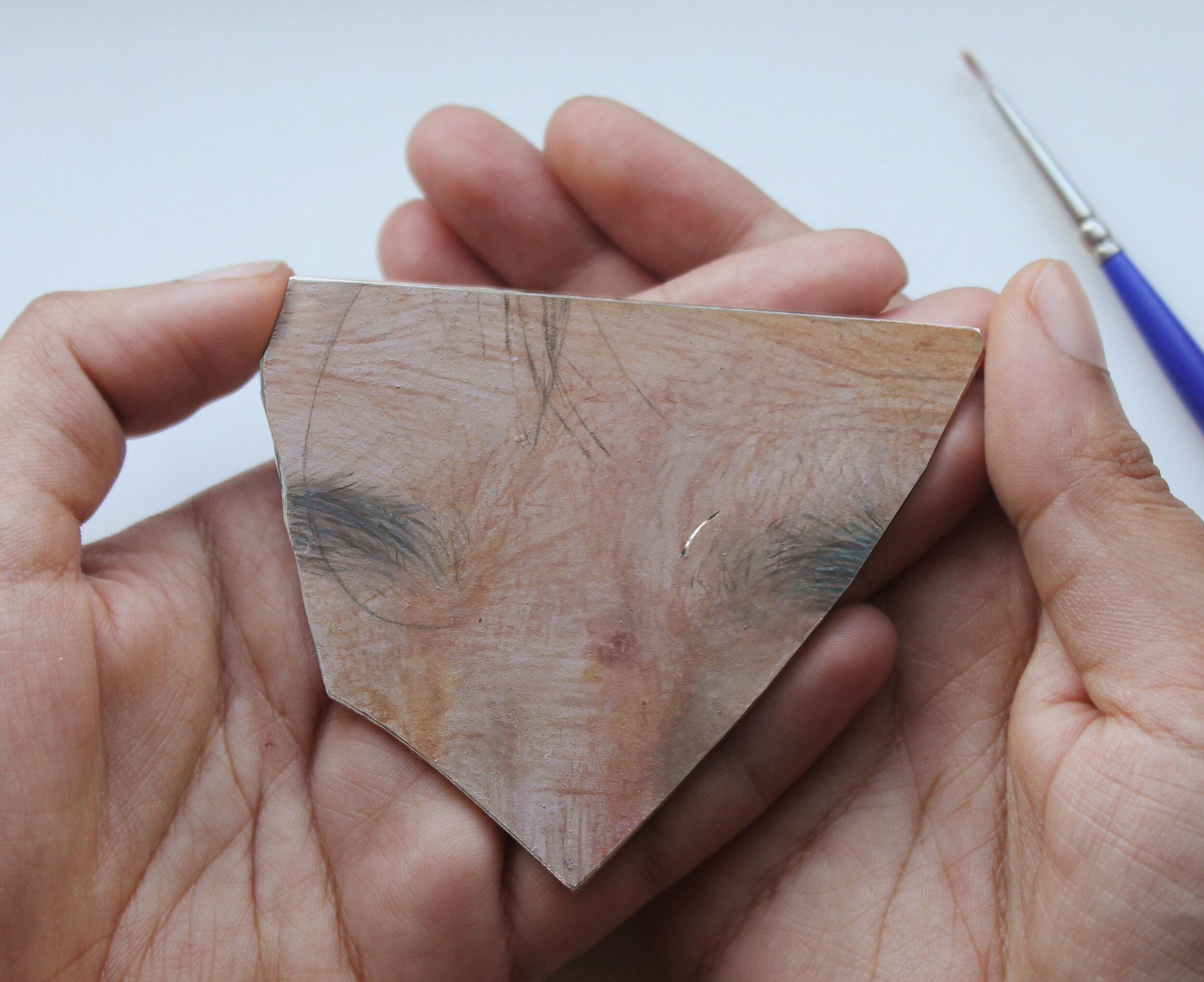

See a scar here? That was when the anorexia became bulimia. My parents had been watching me because the doctor said to. So I started eating and throwing up, and then bingeing and throwing up.

I went to a store. I don't know what store it was. I can't remember. I was 17. And I filled up my backpack with food. I already started bingeing. So I was in this obsessive mode, and when I was on my way home, there was a hill. I didn't ride my bike that much back in high school, and when going down the hill, the backpack shifted. I had so much food in it that it threw me off the bike and I slid on the street and hit my chin onto the curb. And then I thought, "I can't go home like this.”

I can’t ask my mom to help me, because she didn't know how bad the eating disorder was. I hid it well, or at least I thought I hid it well. If she sees the blood on my shirt, she's going to see this giant backpack too. So I went to a neighbor's house that I'd never met. I think we just put a Band-Aid on it. And then I went home and then hid the backpack.

I did a lot of research on eating disorders afterwards. In college I tried to do an art project on it. Back then, when they released me from the hospital after two and a half months, they told me "You don't have an eating disorder. You have a problem with your father." Nowadays, we understand it’s all related. But back then, I didn't. My issues with my father were like any immigrant parent who makes you study all the time and doesn't let you do what the other kids do all the time. I forget what the word is. He was strict. So it was kind of like a silent rebellion, like how anorexia sometimes can be a silent rebellion. Many people think it has to do with wanting to be pretty and skinny right? But I don't think that was the main issue. Everybody wants to be pretty at that age. But I think it was more about also wanting to just disappear. My ideas about it conflict, but the other one was not wanting to mature. When you're anorexic, you lose your period and your breasts get smaller. So you have a very boyish figure. Even now, I don't think there is [one specific reason] for it. It’s about control and independence, identity…

After the hospital I went directly into college. One thing led to another. I began drinking. I still binged and purged.

Then I went to China to teach English. And that's when it all stopped.

I started traveling and learned about my mom's family and about the different people that are there. I fit in - on the outside. When I'm speaking, it's obvious that I was raised differently. But in China, nobody is staring or saying anything to me. They had a different respect for women. They don't catcall women. So I ended up staying there for three years.

When I went over there, I was actually a professor. Now I'm all of a sudden a professor. Normally, you need a master's degree to teach English, but I got the job because my great grandfather used to be governor of the province and a general in the army and helped start the school there. So they were just like, "Well, you're a teacher." That's how I got that job. I guess [what made the difference is] how I felt teaching there. I felt like I had some purpose now. I enjoyed it and the students liked me.

And everything was so cheap there. My rent in 1996 for our three bedroom apartment was $60 (USD) a month. In 2008, when I went back for a Fulbright Scholarship, my rent for my one bedroom apartment downtown was $175 a month. My phone bill was $7 a month.

I was traveling and researching all these minority groups. There are 25 minority groups in that province and my school was for students of these groups. I don't know how impassioned I was back then, but in my artist statement now, I say that [I was impacted when] I saw people who looked like me when I looked in the mirror. People who were bigger, or who had curly hair or darker skin. I didn't realize so many Chinese people here are from Southeast China. They just look a little different.

I started taking daily photographs, and it helped. And then I started traveling in sort of a reckless way, because I was just going anywhere. I didn't know where I was going, I didn't know where I was going to sleep. I wasn't totally fluent [in the language,] but I learned to read Chinese to travel. And no one's paying attention to me. And I have a student ID now, so they don't even know I'm American. I enjoyed the anonymity.

The hotels were either 20 cents or 40 cents a night. Really dirty. I could have afforded a little bit more. But there was something about it, there must be a reason I did stuff like that. I started taking pictures of all these different people in traditional clothing, and rituals. I didn't like Chinese food when I went there. I didn’t like rice. It must have been psychological. But after a year, I started liking rice. And now, I love that kind of food.

When I was traveling in south China, I would meet lots of people. A lady on the bus sat next to me and asked where I was staying. Because women, especially young women, didn't travel alone ever. I don't know what I told her, but I didn't tell her I was American. I told her I was staying at the police hotel. I read there was a police hotel there. I don’t know how I got that information, there was no internet back then. When we got off the bus I helped carry her fruit. She looked at me and said "You're not staying in a hotel. You'll stay with me." And then I stayed with her and took pictures around town.

A lot of circumstances were like that. I remember one time I wanted to take a photograph of the poppy fields on the border of Burma. So I got a motorcycle taxi and told him "Just take me to the fields and leave me there. I'll spend the night somewhere." He said “they don't have hotels there.” I said "That's okay, I'll figure it out."

When I got there, I took one picture of a poppy - it wasn't a big field. And then I started to walk back and there were no houses, no nothing. I figured, I guess I could sleep in one of those bushes or something because it wasn't cold. I still only had my little Jansport. And then he actually came back. He figured I wouldn't be able to find anywhere to sleep. So he came back and didn't even charge me. So just stuff like that. Feeling cared for and protected by some force. By a group of people. Which was not happening where I grew up in New Jersey.

The world is bigger than you can imagine and will open up to you in time. So don’t worry so much. Your choices don’t all need to be understood, even by those close to you.