Creative Beast

“With queer domestic violence, intimate partner violence, it's not talked about a lot, so it can feel very isolating and confusing, in part because our narratives don't look like the dominant domestic violence narratives. I am honored to have an impact on that conversation and hopefully make that something that more people are aware of. My hope is always more societal level healing and more space for vulnerable, honest conversations.”

A Warrior’s Birth, Heather Marie Scholl

A Warrior's Birth was the first work in the series, Resurrection of a Victim, that I conceived of. I was still active in the abuse and trying to separate from it. I needed the boundaries and self protection of A Warrior’s Birth. As I moved through creating the work, [I asked myself], "What do I need to talk about? What needs to come out?" Poetry started coming. I remember being on the bus in New York and having this weird little pad that I would scribble [on.] I hadn't written poetry since bad teenage stuff. It became a way to process, a way for me to route into what's actually happening versus the gaslighting and the delusions of an abusive relationship. The act of making this work was profound in believing myself, first and foremost. That was a huge element of it.

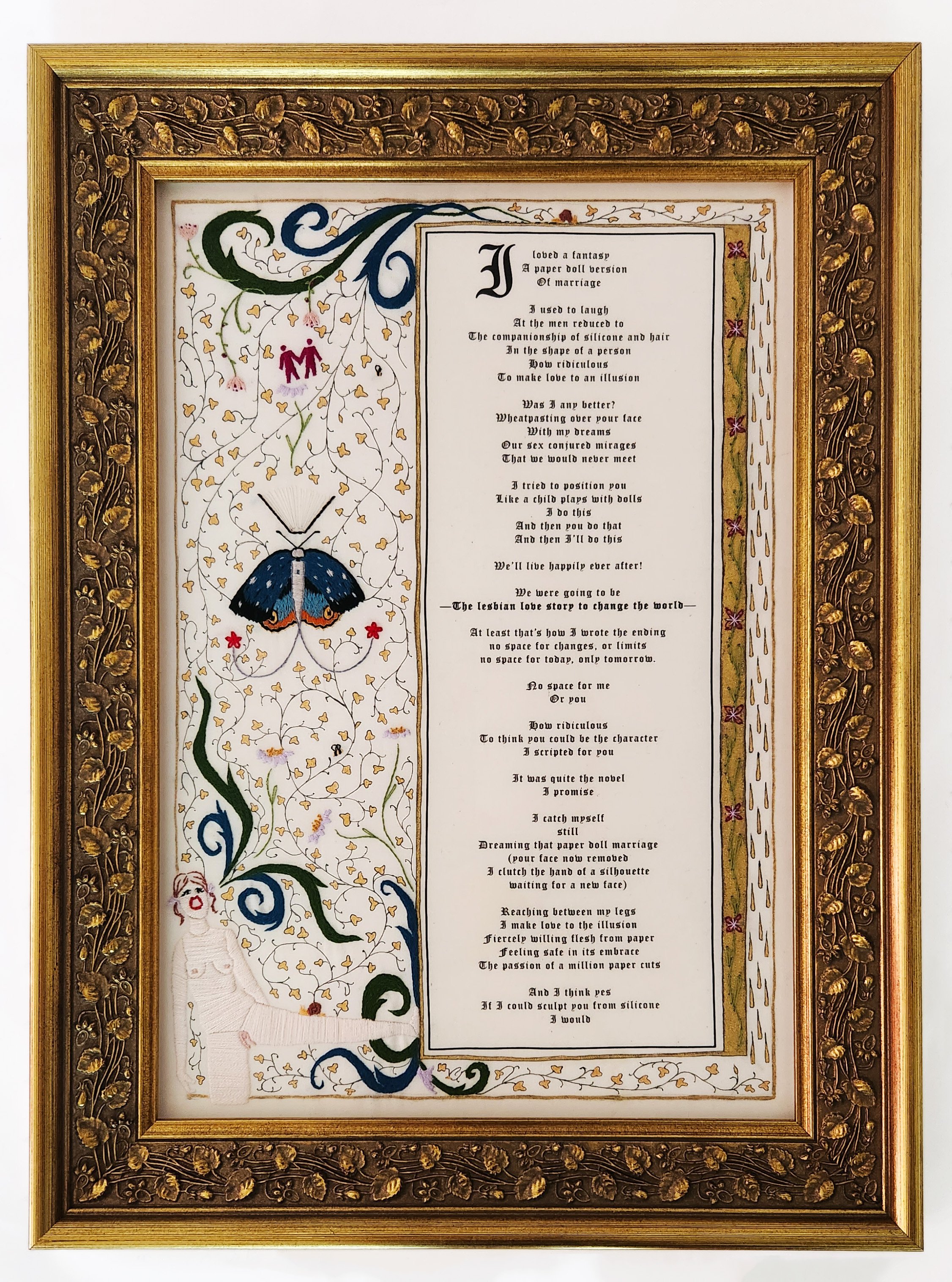

Paper Dolls, Heather Marie Scholl

I have a lot of old self-harm scars. That was a past version of [myself, who thought] "I don't know how to deal with these feelings, this trauma that I cannot control and have no power over” versus the stitchwork where I take agency over my life.

My relationship with this work is different from most audiences. I see joy in this work. That sounds weird, but there's pleasure in the making. There's also the release of it. I also see the humor that I put in the work, like through the use of animals and other symbolism. The first regular support group I went to, we would sometimes get kicked out of the church because we were giggling so much. You think of going to a support group around trauma and relationship issues as being really heavy, but there is a lightness, even in the dark subject matter.

[Art is] emotional processing as well as a source of my activism and spreading information. I was always an artist from a very young age. I was not encouraged towards it as a realistic profession. I didn't take it seriously for a really long time. I [studied] race, gender and sexuality, and then I did fashion design. I started doing hand beading and hand embroidery on garments. When I moved to New York everything changed, [sometimes] physical moves help shake things loose. I realized art allowed me to explore issues of race and gender, and I could still use the fashion crafts that I learned over those years. My main calling became clear.

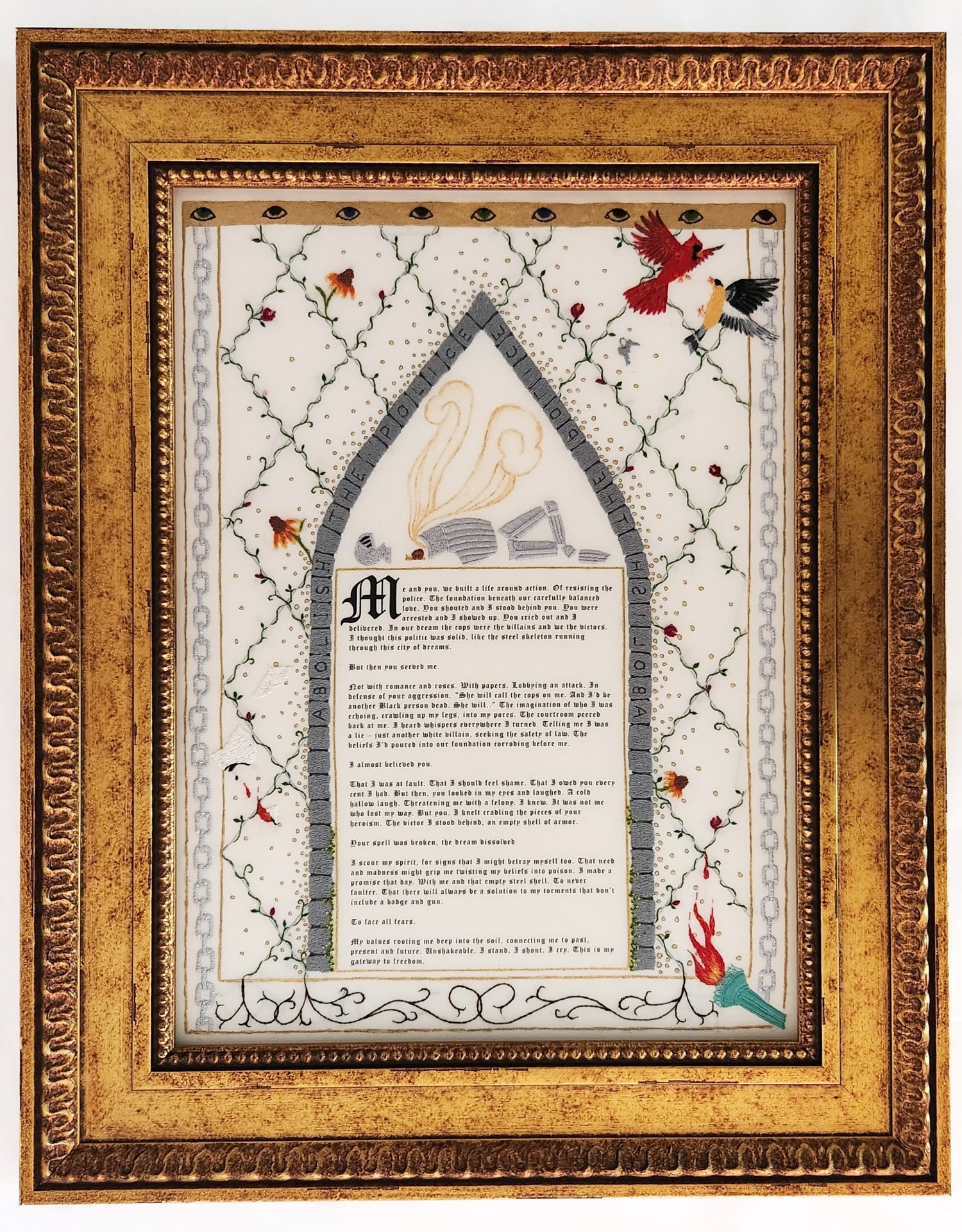

Because of my academic past, I like understanding history. I want to have more conversations about historical context. As my work continues to evolve, I am asking how can I bring all of this together? How can I talk about our history of racial violence and the way that that impacts our present, while also talking about personal traumas? Right now, I'm trying to explore some of the racial origins of domestic violence laws and investigating my family's southern history of domestic violence as well as racial violence and different ideas of womanhood and family.

Abolition & Love, Heather Marie Scholl

Craft is an act of intimacy itself, and that's what I really like about using it in my work with really difficult topics. It brings an intimacy with strangers just by nature of the material, then it pulls these conversations up and makes them more possible because of that. Having an audience that's interested in leaning into that space has been my desire, trusting that it will have a meaningful impact on the people that it needs to. With queer domestic violence, intimate partner violence, it's not talked about a lot, so it can feel very isolating and confusing, in part because our narratives don't look like the dominant domestic violence narratives. I am honored to have an impact on that conversation and hopefully make that something that more people are aware of. My hope is always more societal level healing and more space for vulnerable, honest conversations.

Having support people has just been essential for me; having safe people to decompress and to process it with. I have people that I shared the work with that I really trusted, both with my story and with my art, to support me through that and remind me, "You can trust your own experience. You can do this." I think it's pretty common for DV survivors to isolate, so leaning into the opposite of that has been essential. I joined 12 step groups, [and it created an environment] where I began to be able to speak honestly about my experience. Having a consistent space to turn to that included that kind of emotional intimacy was valuable, to just keep processing out loud.

Early [in the] healing process, [I recorded] what other people thought were my best traits so that I could remember those and hold them close. One person called me a creative beast. Not just “creative” but “creative beast.” That's totally fucking awesome. After a discussion with a friend I wrote “How can I do dangerous work tenderly? '' I think because of my own survivorship, I forget that I have done dangerous work. And then I don't take care of myself appropriately given the dangerous work I'm doing, whether that's my personal trauma work or the racial justice work that I've done. Its a reminder to treat myself tenderly as I do it.

Enough Part 1 and Enough Part 2, Heather Marie Scholl

Liminal Hearing of Queerness, Heather Marie Scholl

The video work is of Riis Beach in New York City, a site of safety and healing for the queer and trans community for many generations. There is something really beautiful and sacred about it that I can't put into words. It’s a space in nature that’s specifically queer. I don't have to say anything, I don't have to be anything. I don't even have to talk to anyone if I don't want to talk to anyone, and it can still have a healing impact on me. I can still feel connected to my community that is there and the community that is in the past, just by being in that physical space. [In a voice over to the video] I got people aging from 16 to like 67 to read pieces of a poem. It is about exploring a past and future and connecting to those lineages [of those] who have gone before and survived and found joy.