Heroes

“There are a lot of things I would tell a 15 year old me…Things are not going to work out. Your best case scenario will not happen. But that's OK. There's this attitude that you'll get out, you'll find your tribe, and you'll get that life that you want to get desperately and you think is unattainable. You might not get that life. It might not work out that way. But that's not a bad thing either.”

The day after the [2016] election, I went up to my sewing room and basically made what I call a Rage Quilt. I just took every piece of fabric I had, no matter how unrealistic it was for a quilt; faux fur, everything, and just sewed every scrap together. I needed to do something that let me get my anger out, but where I won't hurt myself or others. I've been sewing long enough to know that if I'm at a sewing machine, I can be grinding my teeth, but I've got to be focused on what I'm doing.

2016 marked a serious shift in my [art]work. I grew up going to hardcore shows and being very much involved in a kind of punk scene. Although it was distinctly political, the form and formal properties, the political talk was very aggressive and very masculine, macho and aggro. I could clear a pit like nobody's business. Obviously, look at the size of me.

I started to think after I did the Rage Quilt. There was this realization of if I want to see change in the world, A, I have to embody the change I would see and, B, the form and the content have to mesh. And that led me to doing a sound piece - I took audio from Ronald Reagan's "It's Morning in America" and Donald Trump's "Make America Great Again" political advertisements and spliced it up into these beautiful chimes. It's like the most calming, peaceful thing. I'm going to take anger and rage and everything I see wrong in the world and make it beautiful. I ended up getting shortlisted for the Fleischer Wind Memorial Prize out of that.

Through that experience, I ended up having a lot of conversations with friends of mine from all different kinds of progressive and diverse walks of life. No Republicans. I talked to a sex worker that's a friend of mine. I talked to a progressive, evangelical Christian. I talked to a performance artist. I talked to all these people who embodied a perspective or a reality or an identity that I felt was more of what I wanted to see in the world. It was a really long process, it lasted about six, eight months.

As I was wrapping it up, I was coming out of the [art studio] one day and this friend came up to me. There was a farmer’s market and I had been at the stand where she was working at. It had been a while since I had seen her, and she was all bundled up. It didn't occur to me that it was her. So I left and I was walking up to the darkroom, and she tugged at me from behind and said "It's me, I think you need this." And [she gave me] a tube of lipstick. I thought “I had no idea why you think I need this but ok.” And that led to the first photograph.

From the series The Hinterlands

|| CW: Transphobia

I started making dresses to wear in the photo shoots. And then I liked them. And that's sort of leading into me wearing them, not just for the photo shoots.

I was in a show of one of the first photographs from that series that I was really proud of down in Gettysburg College. I drove down there to drop the work off and that weekend there was a pro-gun biker rally. I'm walking down the Main Street in Gettysburg and I'm dressed how I usually dress now. And there are bikers with iron crosses, and it's really not looking good. This could go really badly. I didn't have a change of clothes. I'm six foot eight. There's no way I'm blending in. I'm conspicuous. But then this weird thing happened. None of them flinched. I've gotten worse cat calling on first Friday in my hometown than I ever got with all these big, burly biker guys because, quite frankly, I'm bigger and burlier than them. That was the first time I presented authentically outside of my hometown.

I felt like a superhero that day and I was conflicted as hell about it too. It was a byproduct of my size, which I have nothing to do with it, I have no control over it. And I have so many friends, especially trans and queer friends, that they can't do that. They present authentically inside the art center, but they literally get changed before they walk out of the art center. They know that one foot outside the art center when they're presenting authentically, and they don't know what's going to happen because they're not six feet eight inches tall and 350 pounds. It's empowering, but at the same time, it's fucked up that, for no reason, I'm able to be something that so many other people that I care about and love can't be.

I started to think about the fact it's an amazing privilege on one level, but it's also a burden on another level. Now it's a privilege at 40, almost 41 years old, it's a privilege. But looking back, [my size] was always something that was depressing. It took me till I was 30 to realize it. If I had realized I'd been able to be whomever, to put the pieces together and be in an environment to be able to do it, to have the language to even be able to describe what I was.

|| CW: Bullying

I was a freshman in high school and the gym teacher at my high school was, in my opinion, a raging sociopath. He was just a son of a bitch on multiple levels. Unfortunately he is also one of the winningest basketball coaches in the state, so people don't know this and think highly of him. Beyond that, he also insisted that, because he is a basketball coach, whenever it rained outside, we played basketball. And it was always shirts and skins. And I was, by default, and by his rule, always on skins. And I was a heavyset kid, and my nickname for a while was "Tits." And eventually by the end of my freshman year, I couldn't take it anymore. And I tried to explain it, I tried everything I could think of.

I had breast reduction surgery and that whole experience for a number of reasons is very traumatic. Reason one is that I had the surgery the summer between freshman and sophomore year. I was still on Skins and now I had scarring and disfigurement of the nipples.

They were still harassing me mercilessly. So not only did the bullying not go away, but I think on some subconscious level, I gave them something new to replace it with. And it was further compounded by the fact that I ended up having an infection at one point in the process. It was grotesque and pretty gruesome. So I won't put it in details if you might want to eat at some point in the rest of your life. I still have a lot of sensitivity and agitation in the region of the scar.

And ultimately, it fucking didn't make anything better. I think if I could tell someone thinking of having plastic surgery, "Think long and hard about it, pending on why you're doing it.” If you're changing something about your appearance because you think people will stop bullying you, people will leave you alone, or you could remove the reason you're being bullied, you can't. You can remove it, but the surgery won't remove it. What will remove it is being okay with who you are. Whatever that means. Now, if that means transitioning - whatever it is that makes you. That's what you have to realize. Sometimes that can mean something surgical or medical, but sometimes it means just accepting who you are. And for me, I really thought if I had surgery, everything would be better.

I actually made a piece when I was getting out of Sound art. But it's from that same body of work that I called "No More Heroes," where I took a trophy that I'd gotten playing football in junior high and smashed it to bits and then took a picture of the smashed-to-bits trophy. And I never returned to the piece, but I wanted to for some time. It just doesn't really mesh with what I'm doing now. It's been glued back together and I want to re-photograph it. Because after I did that, I met some of the people that I really idolize and they were amazing. Not all of them, but some of them were exactly who I hoped they'd be. And that was so encouraging.

There are a lot of things I would tell a 15 year old me, some of them related to this. But a lot of them not. I think for me, it would be two things. One, be patient. Two, things are not going to work out. Your best case scenario will not happen. But that's OK. There's this attitude that you'll get out, you'll find your tribe, and you'll get that life that you want to get desperately and you think is unattainable. You might not get that life. It might not work out that way. But that's not a bad thing either. My ideal life when I was 15 was me having a quote unquote "normal life." Being like everyone else. And that never happened. But I also got to hang out with friends of Joe Strummer at a Lou Reed concert. I also got to hang out with my heroes. I've gotten to do amazing things. I got to meet with people who weren't heroes but that were really famous and find out they were douchebags. And that was okay, too.

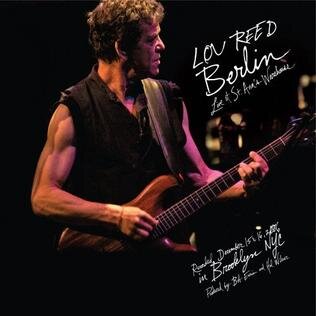

In 2006 Lou Reed performed his album Berlin front to back in Brooklyn. And when I heard about that, I knew I had to go. I love Lou Reed. And then to make it even better, Sharon Jones was performing, Sharon Jones and the Dap Kings and ANOHNI of Anthony and the Johnsons was there too. I got tickets. I went to that. And they had a meeting area while he was getting ready in the back. There was a big curtain that separated like the bleachers that we were sitting on from this other area. I had gotten something to drink and was walking back from where the bar is.

And this woman jumped out in front of me. She's like, "have you ever had your picture taken?" And at the time I was I was like, "Well, I have a background in photography, but I don't think that's what you mean." And she said, "I need to take your picture." She never ended up taking my picture. It was Kate Simon, who was Bob Marley's personal photographer and shot the cover photograph for the first Clash record, the self-titled one. And I spent the night hanging out with her and a poet named Jillian McCain, who co-wrote "Please Kill Me" with Legs McNeil. And we just spent the whole night talking about music and stuff like that. And it was just amazing.

That's the other thing I would tell a younger me - "The fact that you stand out is not a bad thing." When I enter a room, I own that room because everyone is like, "Holy shit, how tall are you?" A little old lady saw me and she's like "You're so tall!" Then she's like "Those are awesome shoes."

I wouldn't have had that experience at the Lou Reed concert if I didn't stick out like I did, if I was just like everyone else, every other 20 something year old at a concert because there were plenty of them. He probably would have never asked me if I had my picture taken. The scars are that kind of thing. I wish I could tell myself that you don't need to do anything to make you who you are.

Throughout high school, nobody in my school thought of me as the artist because I wasn't in the art classes. My freshman year of high school, my art teacher sat me down and said I had no talent, and that I should be a bricklayer. That's about all I was good for. Luckily, a former student teacher, who I had really bonded with, also opened a studio. And it kind of became a haven for me, an Island of Misfit Toys. It was literally built from an old city jail from back in the 1920s where an ancestor of mine was actually a prisoner at some point. My mom's family were in speakeasies back during prohibition. Now it's a nightclub and it's horrible, but when I was in high school, it was an art center, and there was a group of us who all shared studio space there.

From the series Unicorns

I didn’t get into a single [college] I applied to. My parents convinced me to take some classes at the local community college. I took a photo class and just fell in love with it. We took black and white film photography, fine art photography, color photography. This was the late 90s, so we were still doing color printing. Digital wasn't really there yet. I maxed out on the darkroom classes at this community college. And they now have a photo major, but back then they didn't. So I transferred to my dad's alma mater and got an undergraduate degree in Studio Art with a photo concentration. And then you graduate, and they don't let you keep borrowing the cameras. The cameras are very expensive, so I got out of photography within six months of graduation.

Fast forward seven years. I had a kind of family crisis in 2007. From 2006, I hadn't been making art. But during this family crisis, I fell back in love with painting and started immersing myself in that. I took an independent study in painting at Bucknell University. I ended up getting a painting studio at the Pajama Factory when it just opened. There actually weren't studios yet. They put me down at the end of the hall and said, "We won't charge you until we get the studios built." They thought that would be a month. It would be six months. So that basically became me putting my portfolio together, I had six months.

I applied to a couple different [grad] schools. One of them was MICA. I was told by one of my undergrad professors that I shouldn't even apply to MICA, I had no chance of getting in. I got into the Post Bac program, took that, realized through that process that I was very good at understanding the conceptual framework of what I wanted to communicate, but had really none of the technical skills. One of my professors said to me at our final reviews, "I look at your work, and it's like you never learned how to paint. But you're standing here, so you must know how to paint." I really don't. It became apparent to me that I should apply to PAFA because they had a technical rigor that would be just the thing for me. By the end of my first semester, I had a critique with a curator there at the time. He looked at me looking at these huge, gigantic paintings and said, "These aren't saying what you think they're saying." I said, "I know." And then he said, "Well, what are you going to do?" I said "I have no idea." [He said,] "You don't have to paint, do you know that?"

And it was a revelation that I didn't have to be a painter. I was working with a lot of text. My God, look at Barbara Kruger. Look at all these artists. And I love all their work. But it wasn't what I was trying to do. So it was this revelation. I didn't have to paint. So all the paints went in the corner. I just started kind of fucking around with stuff. And around that time, I sold a piece that I did while I was at The Pajama Factory. My mom's uncle, he's since passed away, but he was extremely wealthy. There's a museum up in Connecticut that's got a wing named after him. One of his sons bought this painting. And it bought me a digital camera.

Within a few years after that, I took over the darkroom because the founder, a previous director, was retiring. And once I got my first large format camera, it was off and rolling. I did an artist residency program and I really got to dive deep into photography. And that was right around when I started taking the pictures of myself, as they are now.

My teachers never really thought I was any good, but right out of college, I got a bunch of very high profile shows. I'm making all this work. I wanted to be seen. And I've got a show out in L.A. and I got a show at Deitch projects in New York City. All of a sudden, there was this realization that everyone in my small little provincial town hates my work. But this person that hung out with Andy Warhol loved my work enough to put it in a show. All these amazing, talented people. And then me. Although I found the experience exhausting, it was nonetheless this realization. Some people will love your work. Some people will hate your work. That's okay. Not just because people I respect like it, but because this realization of their opinion is just that.

And still, it's weird, in my hometown, in the arts community, I'm very well known, very well-liked. But if you were to ask most people in the arts community who are the really, really great artists, they never say me. I'm like a gadfly. I'm like, "Oh, they’re in everything. Everyone knows them. They know so much stuff." But my work is the last thing they mention. But about half hour from where I live, there's just tiny, tiny town called Milton. It's literally in the middle of nowhere. It's right off of Route 80. And it's weirdly a haven for art. The art critic for The Wall Street Journal lives there. There's all these really big art world people and they love me. Whenever I have something, they're like "Let us know, we have to be there." I think that's why I'm welcomed there in a way that Williamsport is still trying to figure me out. They don't have a language for me yet. Milton? "Oh yeah, we get them."

The biggest thing I would tell my younger self is that all the things that have made me stick out would one day be virtues, would one day allow me to be who I am. And that ties back into the whole superhero/heroine thing. All the things that drove me nuts and to some degree still do. There's a lot of things about being my size that is a pain in the ass. But the things that are awesome about it are pretty fucking awesome.