so many skins, since

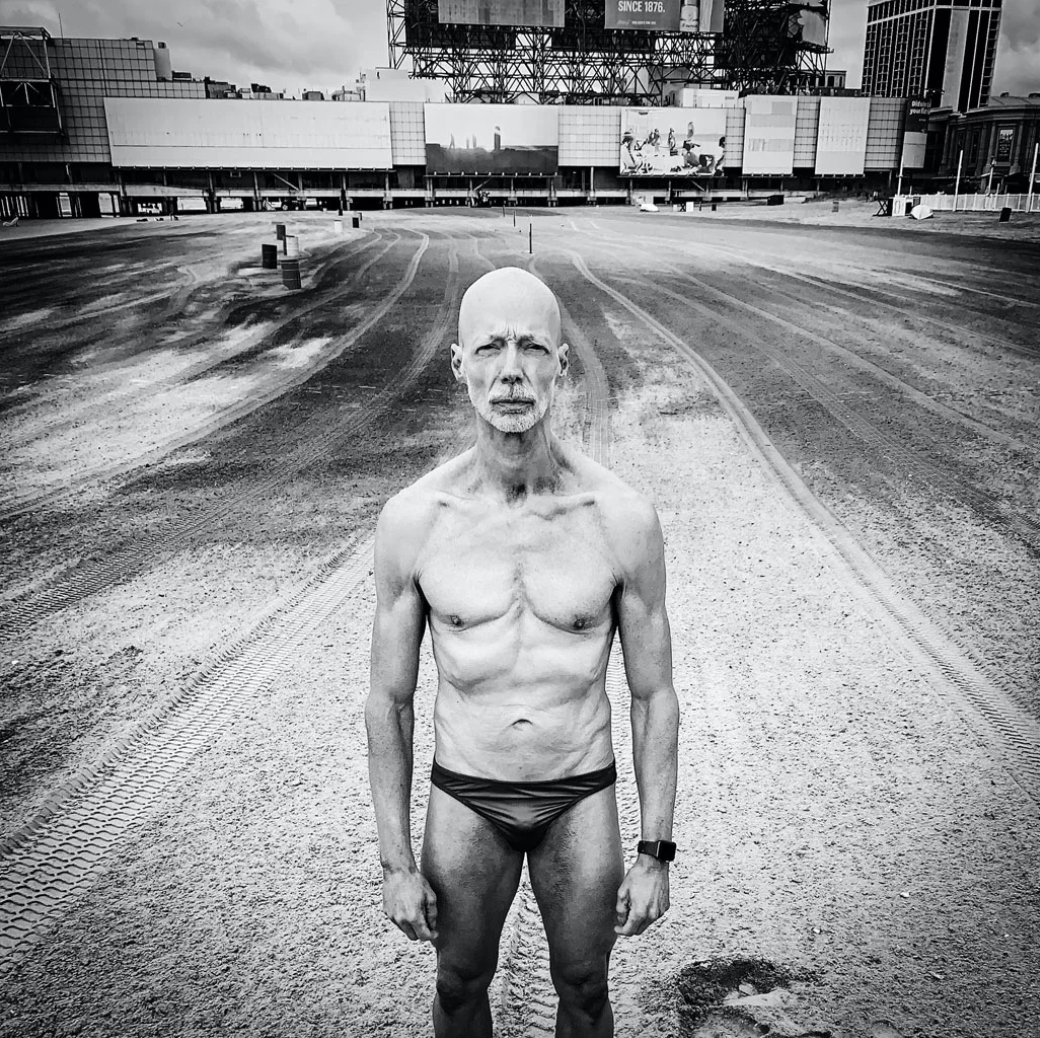

Brian, He/Him

“On this ordinary day, I marvel at how much the world and I have changed. That boy, who was almost killed, has come so far. I have since lived a life of my own making. A life I am proud to be enjoying and sharing with you.”

Arc, 2020

Arc, 2020

In January 2020, [I created] Arc, this big structure took over the whole gallery and you walked underneath it. The inspiration for this piece was a celebration of the impossible. The ironic thing was I wanted to start off 2020 really positive; it’s an election year, right? We're not going to be filled with doom and gloom. We're going to do the impossible. I'm going to have twenty five thousand bamboo skewers, and I'm going to get these things to stand up in the air. I had to assemble it between Christmas and New Year's while the shop was closed. They were built in big, long sections, and then when the shop was open for two days, these things were jutting out over our heads.

The piece was all about hope and expressing insane optimism, and then the pandemic happened. (laughs) But with Arc, that was the impetus of it. Did it translate in the final piece? Was it important for a viewer to know that's where the [idea] started? Not really, because it's about their experience. I want the viewer to find their own way in it and have an experience with it that's theirs, not something I'm demanding of them.

My trainer, he doesn't understand art at all, it frustrates the hell out of him. When he came to see this piece, he walked up and he said, "What am I supposed to get out of this?" First, breathe, and just be with it. When I see pieces, I'm open, like "Oh what is this? And how do I relate to it?" And I realize that's the difference between people who get art and people who don't. "I need to understand what this is" - You don't have to understand it all.

||Cw: Trafficking; mentions of sexual violence

It's interesting because I think I have a different approach [with my art]. I want to force people into a perspective and have them go through that exercise of contemplating something new, and you just let them sit with it and get what they get from it. so many skins, since was exactly that. It was like, "this is what it is."

so many skins, since, 2021

“Here, on a crowded beach, is where I met the man who kidnapped me in 1974. Decades later, I stand for a moment of reflection. On this quiet morning, an advertisement grabbed my attention. It’s a PSA for the National Human Trafficking Hotline. The bright message sparked a revelation. What would have once triggered anger and even shame, revealed a deep gratitude. On this ordinary day, I marvel at how much the world and I have changed. That boy, who was almost killed, has come so far. I have since lived a life of my own making. A life I am proud to be enjoying and sharing with you.”

To be on that boardwalk, to see that sign there. That was my big secret. Those [were] the words I could not use about the entire experience. And to have it blaring. It should have been a nightmare [seeing that sign], but it's not. In fact, I'm going to go seek it out. And of course, the day I went back, I [found] myself with the tripod, 40 degrees out, stripped down, and there's a cigar shop there with guys hanging out in front of it. I knew I didn't make any sense to them at all, and I didn't have to. It was liberating.

The weird thing was after [what happened], there was a week of school left. And I'm 15 years old, right? I go to school and it's that Monday morning. In homeroom, the phone rang, and I knew it was the assistant vice principal’s office. I go straight there. [They told me I] was going to be an unexplained absentee if I didn’t tell them where I was. And I'm like, "I told you where I was, in Atlantic City." He was like, "Yes, but why?" I said, "To work, I had a job." And he's like, "That's not the reason why." I didn’t answer. He's like, "If you don't tell me why, you will have to redo all the work."

There was no chance of catching up. I decided that if it's like that, OK, I'm not going to [catch up], but I wanted to start over. So I'm going to be a really good student for the last five or ten days [of school]. I had to get my schedule from the guidance counselor because I never went to classes. I didn't even know where they were. I didn't know who the teachers were.

I [had] finally become “other.” There was something about my experience that was so removed from everybody else's. In high school, the social anxiety was so intense, I couldn't walk in the front door. I couldn't stand being seen. I wouldn't go in until the hallways were empty, which didn't make sense because everybody was sitting in a classroom by the windows and they could see me coming in. But the separation of the glass, them not being in front of me made it possible. I found out [much later] that this kid thought I was so aloof and cool. Oh, honey, I was terrified. But he saw it as aloof. I couldn't have told you what two plus two equaled because I was in that much anxiety. I'm glad you thought I just didn't hear the question or thought I didn't care.

And I guess I really did become aloof because it broke the social anxiety. But I remember one teacher saying, "Why are you here? I'm going to flunk you no matter what you do." I'm like, "Fine. Where do you want me to sit?" It was very weird. And then by the next year, I just didn't care. So, was I still involved in the anxiety? Was that still kicking in? I don't know.

I think trauma really throws identity into question. Identity is a funny thing, being known as aloof when I knew I was terrified. It's like I wasn't this meek prey, even then. I had a huge revelation last Monday in therapy. I'm doing EMDR, and I just looked at him, and I said, "No, you know what? The truth is…I was a prize. I was worth him attacking. I wasn't prey. He didn't attack me because I was prey. He attacked me because I was a prize." And that's something I believed my entire life, that I was meek prey. Instantly after it happened, that's who I became, because that's what I believed. So that belief got laid on top. So my identity is twofold there. The question of being prey is always there. Which is this huge disconnect.

I mean, who are you? What do you want? Is it based on trying to heal the trauma? Are you reacting to that? Is this who you are? Is this who you're always going to be?

About identity, it’s like always working to find who you were before then. Not to ignore who you became afterwards, but what got laid on top? What is yours to own and what’s just garbage? But that plays out in my artwork all the time. I made it a mission [that,] if it's an integral part of the piece, I will say it.

It was the weekend after Thanksgiving, and I was working with some old photographs, and I realized, “I've done this before.” In fact, it was exactly three years before that I was working with the same photograph of myself, and that I keep coming back to it, trying to decipher it and place it - not reinterpret it, but it's still this force that I need to deal with, [that] I can contend with. So it's always part of the context, the content. I don't know if viewers need to know that, but I'm pretty cagey about how much [I reveal].

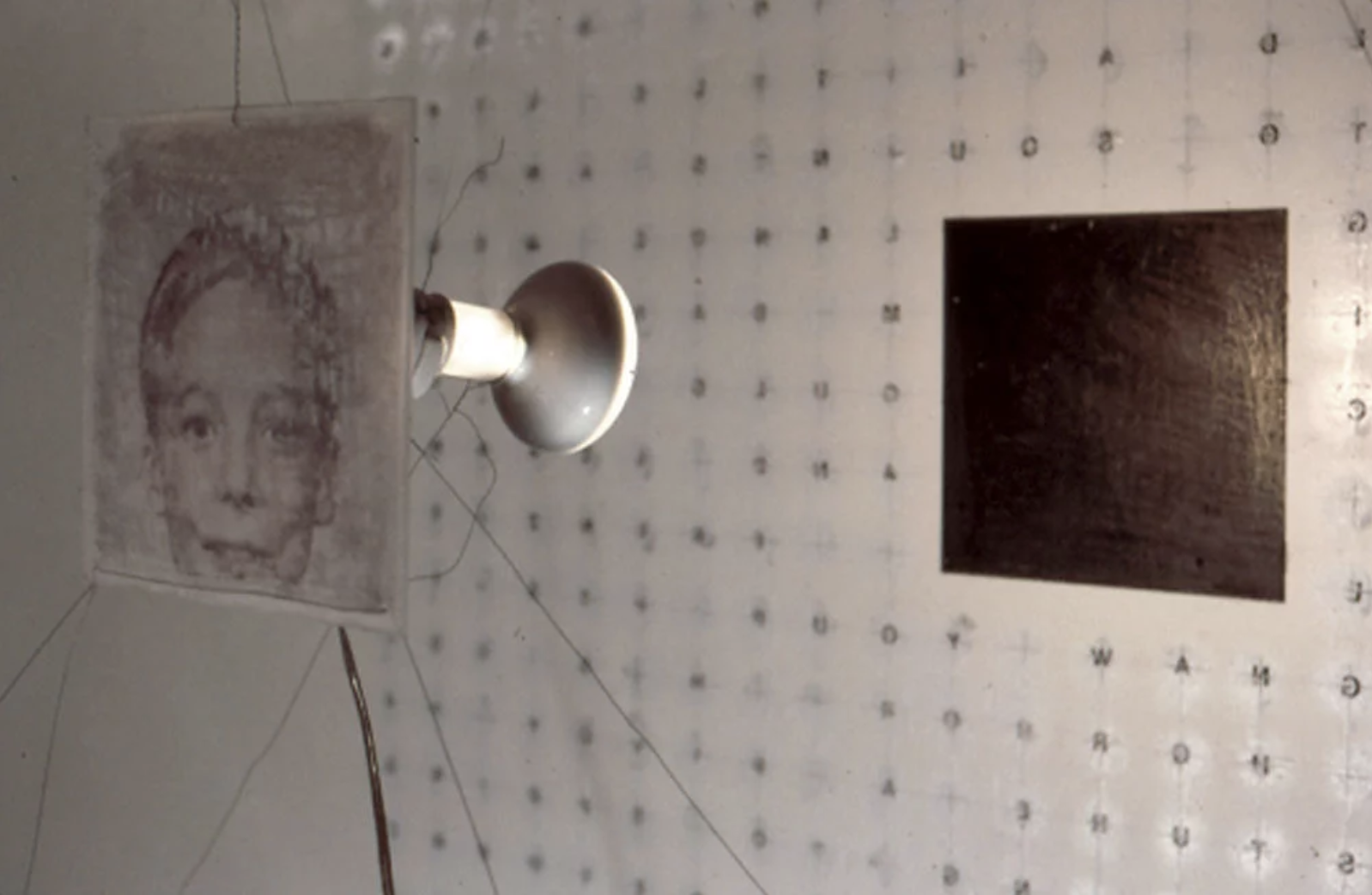

Thirty years ago, it was my second show - my third?- at Vox Populi. And the entire show was called Figurehead (and other talks). I did these poems on the wall. This one's called "My Boy." So I had the text on the wall and it was pretty obscured, but you could make it out. It was a school picture of me. And it was so funny that I was working with that very photograph three years later. I don't remember what I did. But it struck me, it was like "Oh my God, three years ago, [and] I'm still doing it." And I reread the poem, which was very raw.

There were a lot of reasons why it was obscured. I didn't want anyone cluing into what the hell it was really about. I'm about hiding. Everything's hidden, everything's covered up. Unless you get up to [the piece], you can't see it. The text, if you could actually read it, you'd clue in that something happened. And I think I posted [the text] on Instagram along with the collage, and you know nobody on Instagram actually reads anything. So it was fine. I could do that.

[Trauma] has always been a theme in my artwork somewhere. It's not a conscious choice. It's just part of that spontaneous process, I work very intuitively. What is conscious [that] I do a lot of writing about it. I do a lot of posting about it. That stuff's very intentional and I feel driven to do that. And I don't know if that drive is an urge to heal. I haven't figured it out. I haven't figured out why I'm so compelled to be public.

so many skins, since went out to everybody on [our mailing] list. Somebody online - and not a survivor - was like “OK, who's public? And who's not? And why?” And I'm like, "I don't know why, [but] there is a huge impulse to be public with my story." And a lot of that [was] a tonic for shame. I feel a need to do it, and I don't know why I feel that need. I do know I can't second guess it because when I start second-guessing it, I end up in a rabbit hole, and that's when the shame kind of implodes and creeps in there and covers it up.

The public posts are for the people that need to see it. They're not for everybody. It's intensely gratifying when people connect to it and they're inspired by it. When they feel hope. I'm lucky I've talked to so many people. My shame tells me to hide. I can't do that. I will not do that. Perhaps that makes me a poster child or something, I don't fucking care. Yeah, and if it gets on people's nerves, I don't care because guess what? I realized that these aren't the people I'm writing for.

I'm not ready to let it go. I'm not done processing it. I realized it's a lifetime dance. I'm getting it to a place where I'm pretty powerful with it. I'm in a very strong place right now. I'm not in crisis about it, but it's this thing. It's there, it's always going to be there no matter [what]. The word heal always sounds a little suspicious to me. Like, this isn't a wound that's going to close up. Like, "Oh it might not even have a scar." I will grow, but this is in my psyche.

I believe only after 40 years [did I] learn my lesson. It's like, “You know what? You're paying attention to this. You don't need to do it openly in front of someone to be honest and be paying attention.” Also, if I talk to some people, it's a niche conversation. [My survivor groups] are just in online forums. I get a lot of support from them and, being older, I get to give support and inspiration. I have a mission to inspire people to keep going. I know how bleak it feels. I was overwhelmed. I couldn't communicate. I feel a mission to let people know it gets better. It doesn't go away, but it gets better.

Figurehead (and other talks), 1992

Figure Head and Other Talk juxtaposes the mythical innocence of childhood against the vile knowledge of sex, violence and death. The four installations were intentionally dangerous. My use of broken glass, accessible electrical devices and combustible materials was an effort to force the viewer/reader to be acutely aware of their own physical presence.

There was another piece I did at Abington. It's called Call It. My intention was to build this floor to ceiling curved wall of cardboard on its edge. Inside it were these woods, but you can never really see it because of the fluting. The cardboard was cut into strips two inches wide, so you can never get your two eyes to focus on the same thing. You could squint and kind of make it out.

Every light I own was inside it. I was pulling extension cords from other galleries. I had this forest of tinfoil trees there. So when you looked in, there was depth there. It wasn't just a tree trunk. There was an entire forest in there if you could figure it out.

So I was really disappointed I didn't get the wall all the way up [to the ceiling]. I [ran out of] time. I cleaned up, I threw on some clothes, and I came out and my friends were there. And they're staring at the wall. Not at my wall, but they're staring up at the light [projected] on a wall. I had never turned around. I was so obsessed with gluing, gluing, gluing, gluing, that I never saw that the light projected beautiful patterns onto the wall. They're like, "This is beautiful!" I was like "What? What? Oh, that's there." It's so funny.

It was really important to have this impenetrable barrier that alludes to [being] in the woods. [I] grew up in the woods. That piece was very much about never quite knowing what you're seeing. What am I seeing? What do I have locked away? And I don't know. You don't know. And for us to find out and figure it out, you can be really scientific and map it. You can close your eyes and try to figure out there's a tree, there's a tree, there's a tree. But it's really funny talking about artwork becoming something else.

Call It, 2016

The gallery is occupied by a large curved wall, bulging into the space. The structure spans wall to wall, floor to ceiling. Built of hand cut cardboard, the surface recalls layers of sediment. Through the corrugation a dawn tinted light dapples the observer. Behind the wall, light glares through a barely distinguishable forest of vertical lines. Moving in front of the wall, your ability to focus on any one trunk is frustrated by the limited view.

The installation explores the persistent core of memory and the need to stabilize it. Call It attempts to assign a fixed point to an ever shifting, but recurring fragment.

The work originated with running through the woods as a child.

Heavy breathed I dared remembrance to look.

Last time I stumbled on a carcass it wasn't MY dog…

some stranger left it in the woods to rot,

left it in the woods for my run to find,

for my sneaker to get caught in it's brittle ribs…

In a steeled room we hid to test this/heal this.

When I was [in] preschool the next door neighbor showed me all these science experiments. He had built a square boomerang and he was going to go test it. [He asked,] "[Would] you want to come along?" [I said,] "Yes."

We got to the field. It was by a big oak tree at the end of the field, and he said, "Go by the big oak tree and stand under that" because he didn't want me to be by him [when the boomerang] was going to come back. He thought he's putting me in this safe place, right? But he threw it and he hit the tree and it ricocheted off a branch right into my head. He comes out, he picks me up, and he's pressing my head against his chest. And it's gushing blood. At the same time, I just felt so protected in his arms. I never felt that.

It felt amazing. I wasn’t in Kindergarten yet, [but] I wasn't afraid. All that blood and I wasn't afraid. It was like, I'm safe. I'm absolutely safe. This was an amazing feeling. He lays me down and he gets his Mom. And she comes in and she's hysterical and she forbids him to ever play with me again. Then I got the stitches and that upset me too. That was really horrible. But yeah, that's my scar.

A large spindly structure squats in the gallery. Elongated crystalline trestles have toppled into one another, forming a pyramid. Arc was inspired by visualizing darting electrons climbing to a central discharge. It is a chaotic dance, frozen in time caught on a still frame. The piece was conceived to teeter on the structurally improbable. Within its origin myth are vague references to alternative universes, a defiance of logic, a shift in time and a benevolent occupation. The installation questions the boundaries between permanent and temporary, object and experience. Is one more valuable than the other, more noble, more worthy of all that was invested in its creation? The work also continues my exploration of obsession and repetition. Production is a test of endurance and an engaging challenge. But it is also more. The demands contain a self fulfilling purposefulness. Within the repetition is a solace akin to a meditation. I responded to this state with journal notes in the form of photo collages. At InLiquid, Towne Park Place